Uncertainty

The veritable confusing soup that is uncertainty

Uncertanty? That’s pretty easy. Ahhh, not so fast.

Here’s where things really start to get difficult

We all know what uncertainty is, right?

Well, no. Uncertainty is not one thing. Much as we might like it to be simple, uncertainty simply isn’t.

Most people in most analytical situations conflate uncertainy with risk. Let’s start there.

What is risk?

Risk is the possibility that you will somehow lose something or someone you value. It implies loss. Some people talk about upside risk, but that is just flat-out non-sensical, a semantic delusion. Upside implies gain. Risk implies loss. OK so far.

In the previous definition, the key words are possibility and value. Possibility implies uncertainty: something may happen or it may not — the possibility of an event is binary. We may assign a probability to any level of occurrence or any event, but that is not inherent in the event itself; it is an analytic judgment we make and assign it to the event. Also, consequentially, any event occurring may produce a range of outcomes, a further uncertainty.

If we do not value something, we do not consider its non-existence as a loss. Paradoxically, we may feel partial loss more acutely than total loss. The value we assign need not be pecuniary; it may be sentimental or emotional; it may direct or instrumental, relating to the loss of a facility to make use something else in a way that we value.

The idea of upside risk has crept in through repeated misuse of terms and the ambition by some to stamp their authority on a disciplinary field. We can safely ignore it.

Risk differs from uncertainty.

In economics, in 1921, University of Chicago economist Frank Knight drew a very important distinction between risk and uncertainty. He distinguished estimable risk from inestimable risk, which he labelled uncertainty. If we can estimate the probability of an occurrence (of an event occuring, for instance), we can price it, meaning we can value it in pecuniary terms. If we are unable to price it, we cannot deal with it with in economic calculus.

However, as time has gone on, because people have persistently used these terms loosely, Knight’s vital distinction has itself caused terminological confusion — semantic uncertainty, if you will — by applying these terms outside their tight, original definitions. The reason for this is that there remains a lack of certainty around the probability estimation of the risk. There is epistemic uncertainty; that is, uncertainty about the accuracy and quality of the information known about the probability or the relationship between the events on which the uncertainty is based and the event or events under consideration. For example, has time altered the cause-and-effect relationships that gave rise to the observations of events on which the probability is based. Are those causal relationships persistent. If not, what is the utility of the knowledge for judging the probability fo the events under consideration.

In relation to uncertainty, do we really know the character of what we speak? Is our understanding of it reliable? Is what we think to be one thing, really something different, meaning that, over time, its expected response to contingencies will alter. Is it really just A or might it be A+f(b), where we cannot observe (b) and are uncertain of how the event or events under our consideration relate to (b) anyway (that is, confusion over the. functional relationship between our event or events and changes in (b). This is ontological uncertainty. or uncertainty over the nature of reality of objects and relationships between objects (and between objects and subjects, which adds another layer of complication dealt with by Frank Ramsey and Leonard Savage, among others) Yet it all feeds in to what most people call risk (as well as risk in the Knightian sense).

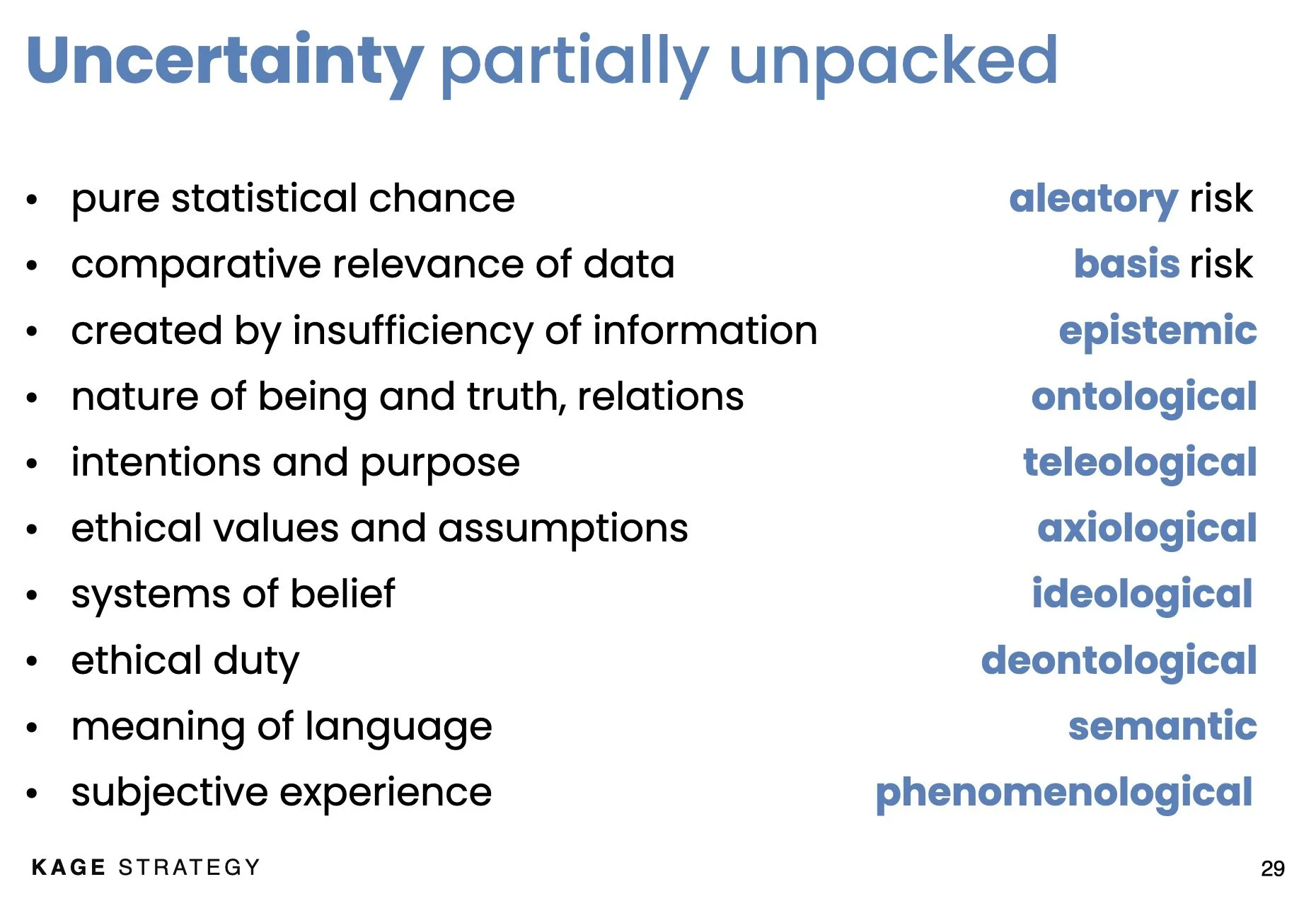

Types of uncertainty

Uncertainty doesn’t end there. Once we factor in other actors, allowing for real human inter-actor, intra-group and inter-group relations (even ignoring tactical behaviours, incentives and multi-group membership), multiple different types of uncertainty exist.

We have already established

epistemic uncertainty

ontological uncertainty (which also contains multiple potential distinctions)

There are others. For example:

Welcome to our world (which is, incidentally, your world too).